Bangalore, Karnataka’s capital state in India, is, with 10 million inhabitants, the third most populated city in the country. Today, Bangalore extracts nearly 1,400 million liters of water from the Cauvery River, which runs 100 km away and covers only half of the city’s needs. The rest of the city’s water needs are obtained from underground water sources that are rapidly depleting and whose quality is also deteriorating. The growing dependence on river water is not sustainable since there are limits to the extractions on this demanded river that flows through many states in which the demand for water for the industrial, agricultural and urban sectors increases more and more.

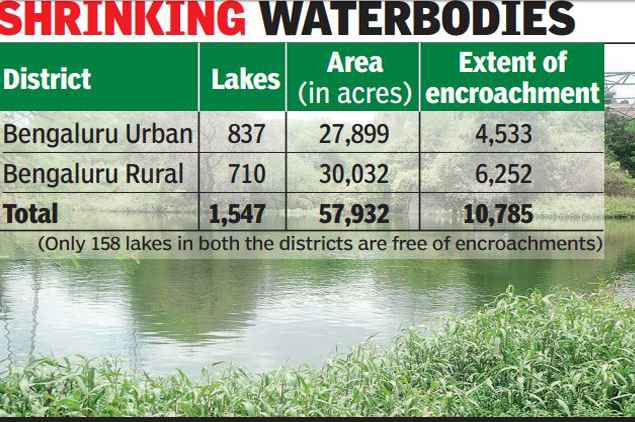

The current Bangalore metropolitan area owned almost 600 of these lakes until almost two decades ago that supplied it with drinking water and water for irrigation, horticulture and industrial activity. In addition, they were important wetland habitats, especially for migratory waterbirds. Nowadays, these lakes are places of serious contamination and invasion and less than 450 survive in various states of deterioration.

The current Bangalore metropolitan area owned almost 600 of these lakes until almost two decades ago that supplied it with drinking water and water for irrigation, horticulture and industrial activity. In addition, they were important wetland habitats, especially for migratory waterbirds. Nowadays, these lakes are places of serious contamination and invasion and less than 450 survive in various states of deterioration.

At the end of the 1980s, important efforts were made by the Government to save the lakes of Bangalore, as a first step towards the use of water to increase the growing demand of the city and as a measure for its conservation as a common good and source of biodiversity. This work failed during the following decades and quickly the corruption and the serious administrative negligence caused its lamentable current state. The challenge now is to alleviate the situation and rehabilitate the lakes and channels that connect them with the joint action of the community and the government and under the supervision of the judiciary.

450 remaining lakes are completely rehabilitated, as well as its network of connection channels, it is foreseen a massive absorption of rainwater towards underground aquifers due to the filtration coming from the lake systems themselves.

When the Environmental Support Group (ESG) began to address this situation a decade ago, most felt it was a futile and dangerous battle against well-organized corrupt forces. Even so, the ESG persevered, organized local collectives and carried out a series of campaigns for the conservation of these lake systems that were complemented with a multitude of awareness workshops to raise awareness of the need to protect these water bodies for the benefit of present and future generations. The intention was to guarantee the recognition of lakes as common goods since they were functional ecosystems that provided a diversity of livelihoods and cultural and social services.

Then the ESG transferred to the Supreme Court of Karnataka a public interest litigation that resulted in two major measures: a new status quo was ordered on the ongoing privatizations and a Commission was formed, consisting of nine government agencies and chaired by a judge of the Court, to develop a comprehensive plan and strategy for the protection and conservation of the lakes of Bangalore for posterity.

With the efforts put in place, the inhabitants of the cities will benefit from open wild spaces, obtaining a variety of benefits for both the environment and public health. Above all, this effort will have significant benefits in a city with high water stress. The poor of the cities will be the biggest beneficiaries since none of these possibilities exists in the current scenario.